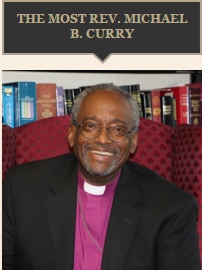

The Most Rev. Michael B. Curry is the

27th Presiding Bishop and Primate

of The Episcopal Church.

Click on his photograph below to visit his website.

Here is an article from the Washingto Post by Michelle Boorstein November 1, 2015, when Bishop Curry was first installed as our Presiding Bishop.

The public face and style of the Episcopal Church shifted Sunday with the installation of Michael Bruce Curry, the denomination’s first African American spiritual leader.

Curry, 62, a high-energy, evangelical pastor, is expected to bring a positive, Pope Francis-like vibe to a church community marked in recent years by shrinking numbers and legal disputes related to gay rights.

“Don’t worry! Be happy! God loves you!” Curry boomed at the close of his sermon to the 2,500 people gathered in the soaring Washington National Cathedral. Preaching from the elevated Canterbury Pulpit, Curry immediately changed the face of Episcopalianism, historically one of the faiths of the nation’s white elite.

Curry, known for focusing on evangelism and programs for the poor, follows Katharine Jefferts Schori, a somber Nevada oceanographer who was presiding bishop for nine years.

Jefferts Schori oversaw a tumultuous period as Americans turned away from the denomination and conservatives streamed out, in some cases triggering litigation over church properties that bled into many millions of dollars. The church has faced the same tensions that other faiths have had for decades over issues such as gay rights and the female clergy, but it ordained Gene Robinson, an openly gay bishop, in 2003. Since then, the church has lost 20 percent of its membership.

Episcopal Church installs first black presiding bishop

In an energetic and multicultural ceremony at the Washington National Cathedral, Michael Bruce Curry became the first African American presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church. He’s been compared to Pope Francis for his open and positive message. (Gillian Brockell/The Washington Post)

Curry focused his installation sermon on racial reconciliation, a cause at the center of what he calls “the Jesus movement” — a new emphasis on evangelism. Preaching in an animated style more familiar to a Baptist church, he told the story of a young black couple who visited an all-white Episcopal church in the 1940s. The woman, an Episcopalian, approached to take Communion. The man, who was studying to be a Baptist pastor, sat in the back, watching to see what would happen when it became clear in this segregated era that there was just one cup from which everyone would drink.

When the white priest offered the cup to the young black woman, the scene was so dramatic that the man shifted his affiliation and was ordained as an Episcopalian.

“The Holy Spirit has done evangelism and racial reconciliation in the Episcopal Church before, because that man and woman were the parents of the 27th presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church,” Curry said, speaking of himself.

The church broke into roars and applause.

“Yes, the way of God’s love turns our world upside down. But that’s really right-side up,” Curry preached. “And in that way, the nightmare of this world will be transfigured into the very dream of God for humanity and all creation. My brothers and sisters, God has not given up on God’s world. And God is not finished with the Episcopal Church yet.”

Racial reconciliation has become a higher priority for many predominantly white U.S. churches. The Very Rev. Gary Hall, dean of Washington National Cathedral, along with the Rev. Mariann Budde, the Episcopal bishop of Washington, in recent years have elevated it in sermons, programs on gun control and symbolic actions such as removing the Confederate flag from stained glass in the cathedral. The question for Curry and other faith leaders is how to avoid the political polarization Americans both love and hate and with which many young people associate organized Christianity.

While Curry focused on overcoming economic, racial, educational and political divisions, he is known as a progressive who was one of the first bishops to allow same-sex marriages to be performed, in North Carolina. He was involved in grass-roots demonstrations in Raleigh called Moral Monday, challenging local and state governments to address the poor and marginalized.

“Is it an understatement to say we live in a deeply complex and difficult time for our world,” Curry said. “Life is not easy. It is an understatement to say that these are not, and will not be, easy times for people of faith.

“Churches, religious communities and institutions are being profoundly challenged,” he said. “But the realistic social critique of Charles Dickens rings true for us even now: ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.’ . . . Don’t worry! Be happy!”

The installation drew a large crowd for the cathedral, including 150 bishops who streamed in together in white-and-red clerical garb. There were at least 75 “watch parties” of Episcopalians across the country, church spokeswoman Neva Rae Fox said.

The Episcopal Church is the U.S.-based part of the global Anglican Communion, one of the largest Christian communities in the world. Its membership, about 1.8 million, was never large, but until recently was home to a disproportionate number of the United States’ business and political elite. Culturally it was considered a proper part of U.S. society, with a refined and orderly worship style. Although that is a somewhat outdated image, Curry’s installation drove home the change as clergy processed to powerful Native American drumming music and an intense rendition of the black spiritual “Wade in the Water.”

“I wish everyone who thinks Episcopalians are the Frozen Chosen could experience this service,” tweeted one attendee.

——————-